The missing piece of the integrity puzzle: politicians' private interests

Federal parliament needs to act against MPs who don’t declare their private interests and restrict gifts, free travel, and hospitality from influence peddlers. Check out our proposed reforms.

Sean Johnson21 September 2023, updated 5 Nov 2023

Introduction

The Federal Parliament's registers of Members' and Senators' interests are similar to a Monet: they look much better from a distance than up close.

First proposed in 1983 by former prime minister Bob Hawke to give the public “confidence in the integrity of its elected representatives”, the members’ register was established in 1984 and the senators’ register a decade later.

From afar the registers look like a tough disclosure system for managing conflicts of interest and reducing corruption risks, with parliamentarians required to declare any interests which could conflict, or be seen to conflict, with their public duties.

The Hawke government introduced a register of ministers' interests in September 1983. At the same time Hawke proposed registers for MPs and senators. He suggested a register for the press gallery too, but that went nowhere.

If an MP knowingly provides false or misleading information to the registers, or knowingly fails to declare their interests, including changes, on time, they can be found guilty under the register rules (resolutions) of serious contempt and dealt with accordingly.

No one knows what 'dealt with' means exactly, but it sounds bad.

Newly elected parliamentarians might think, 'Geez, I better declare all my interests to avoid being in contempt and dealt with!'

But that would be a rookie error.

No consequences

Politicians routinely fail to declare their interests, or not on time, and almost never get in trouble. The registers are more an honours system, that many don't honour.

The most publicised example in recent times is that of former attorney-general Christian Porter, whom the House privileges committee failed to act against over his refusal to disclose to the members’ register who funded his legal fees in his failed defamation action against the ABC over historic rape allegations.

Alleged disclosure breaches are rarely even investigated. MPs are repeatedly caught by Open Politics and the media for not declaring real estate, shareholdings, directorships, junkets and gifts, and in not one instance have any faced even cursory questions from their privileges committees.

Sample of undisclosed interests

- Craig Kelly: Undisclosed purchase of a new home in 2021

- Richard Marles: Undisclosed junket to China in 2019

- Pauline Hanson: Undisclosed property in Maitland NSW.

- Hollie Hughes: Undisclosed company shareholding and directorship; undisclosed trip to Israel in 2022; and undisclosed free helicopter flight in 2020.

- Ted O’Brien: Undisclosed shareholdings in ten companies.

- David Van: Undisclosed trip to Egypt in 2022.

- Peter Khalil: Undisclosed trips to the United States in 2022 and 2023.

- Deborah O’Neill: Undisclosed trip to the United States in 2022

- Helen Haines: Undisclosed trip to the United States in 2023

- Luke Gosling: Undisclosed trip to the United States in 2023

- Janet Rice: Undisclosed trip to India in 2023

- Terry Young Undisclosed trip to Taiwan in 2022

- Libby Coker Undisclosed trip to Taiwan in 2022

- Warren Entsch Undisclosed Qantas Chairman’s Lounge in 2023

Gifts, free travel and hospitality

MPs regularly declare to the registers various gifts, free travel and hospitality from companies, lobby groups, and foreign governments.

The largesse includes junkets, first and business class upgrades, tickets and hospitality to the Melbourne Cup Birdcage, AFL and NRL grand finals, the State of Origin, the Ashes, the Bledisloe Cup, opening nights of musicals and plays, food, and cases of alcohol.

And, of course, Qantas’s tool for keeping MPs compliant and supine, the Chairman’s Lounge.

- Gambling industry sprays hospitality and gifts

- Junkets and influence

- The price of admission

- Flying high: How politicians travel in style

- Donor Kebab: Political donors give more than money

Notwithstanding recent media coverage about Chairman's Lounge, the received political wisdom seems to be that it's no big deal for MPs to accept gifts as long as they are disclosured. But, as we’ve discussed before, transparency has its limits - sunlight is not always the best disinfectant. The mere disclosure of a gift or free service does not necessarily negate its potential to compromise the recipient.

The science behind this is the norm of reciprocity: when someone gives you something it creates a psychological obligation to return the favour. While the norm is not a problem among friends, family and colleagues exchanging gifts, it’s often abused by people, as illustrated in this hilarious clip from the 1980 comedy Airplane!/Flying High!.

So when an MP accepts gifts from lobbyists, rent seekers and other mendicants, we should be wary of believing their claims that they won't return the favour in some way, whether through actively helping or not opposing the gift giver on a regulatory issue, agreeing to a meeting, or facilitating access to decision makers.

Afterall, it's the polite thing to do when people have given you something.

Reform recommendations

We hope we have made the case that parliament's regime for dealing with conflicts of interest is hopelessly inadequate and needs overhauling.

The following recommendations are about ensuring rigorous enforcement of interest disclosure rules, reducing the corrupting impact of influence peddlers on our political system, and requiring MPs to disclose more information about their private interests.

If you have any feedback, we would love to hear from you. And if you support our recommendations, please send them to your local MP and senators and ask where they stand.

1. Establish an independent enforcement body and integrity code of conduct

Part of the reason the register rules are almost never enforced is that investigations can only occur if MPs, or their chambers as a whole, refer allegations of breaches to their respective privileges committees.

As we’ve highlighted previously, while the major parties conduct opposition research on each other over undeclared interests and conflicts of interest, they tend to avoid referring matters to the committees for fear of retaliatory referrals. Lone MPs also don't make referrals as they would instantly become social lepers with their parliamentary colleagues.

That’s why enforcement of the rules needs to be taken out of politicians’ hands and given to an independent body with the power to initiate investigations without a referral from parliament and the ability to make public findings with recommended sanctions such as fines.

The register rules also need to be toughened (more on that in a moment) and folded into an enforceable integrity code of conduct.

Advocacy to date

Independent MP Helen Haines advocated in her Parliamentary Standards Bill 2020 for a parliamentary code of conduct with integrity obligations, a parliamentary standards commissioner to deal with serious code breaches, and a statutory register of interests.

The proposed code of conduct went beyond the regulation of pecuniary and other private interests to cover, among other things, outside employment, accepting gifts, use of public resources, and post-retirement activity.

Alas, the bill did not pass, although parliament might be inching its way there with the commencement of the Independent Parliamentary Standards Commission in early 2024 to police a behavioural code of conduct and the recommendation of the Joint Select Committee on Parliamentary Standards in November 2022 to add integrity and ethical standards to the code sometime in the future.

While parliament ponders whether it needs integrity standards, Open Politics recommends they should also look at introducing a broader conflict of interest regime like the Canadian Parliament’s Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner, who regulates both political figures (ministers, MPs, and ministerial staff), and some senior appointed officials and board appointees.

2. Ban gifts, free travel, and hospitality

Helen Haines' proposed code of conduct would've prevented MPs from accepting gifts, hospitality or other benefits which create "an actual or perceived conflict of interest; or might create a perception of an attempt to influence the parliamentarian in the exercise of their duties."

To our mind a better approach is to simply prohibit MPs from accepting gifts and other benefits as anything of value creates a conflict of interest.

This would mean no more Chairman’s Lounge, junkets, flight upgrades, tickets and hospitality to sporting and entertainment events.

MPs would only be allowed to accept gifts of a nominal value - e.g. cheap pens, product sample packs, calendars, coffee mugs, and note pads - which are typically received in the mail or handed out at functions MPs attend.

The ban would also allow MPs to accept moderate hospitality in the normal course of their duties when engaging community groups and local businesses.

Open Politics recognises that MPs are regularly offered gifts and hospitality from foreign governments and parliaments on overseas trips or when foreign dignitaries visit Australia, and that there is a risk that declining may cause offence and even a diplomatic kerfuffle.

However this risk could easily be addressed by MPs notifying foreign officials of the gift ban in advance of any engagement. Such a system already exists for ministers, their families and staff, with the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet’s gift guidelines stating that “Australia is not traditionally a gift giving country… appropriate opportunities should be taken to inform potential gift donors of Australia’s gift policy [ministers are prohibited from accepting gifts above $300 from private sources and $750 from official or government sources, unless they pay the difference].”

Open Politics also recommends that the gift ban apply to MPs' families, ministerial and other parliamentary staff, the Australian Public Service, Australian Defence Force, Commonwealth corporations and entities, Commonwealth judicial officers and staff, and contractors. Essentially everyone on the Commonwealth payroll.

Ministers in breach of the Ministerial Code of Conduct by accepting Qantas Chairman’s LoungeThe Albanese Government’s Ministerial Code of Conduct incorporates the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet’s gift guidelines in paragraph 3.20 and defines ‘gift’ broadly to cover “gifts or benefits received (including services provided at reduced or no cost).” With Qantas Chairman’s Lounge estimated by Australian Business Traveller to be worth $10,000, every minister who’s accepted Chairman’s is in breach of the code. Even if one quibbles about the $10,000 estimate, Chairman’s well exceeds the allowable gift limit of $300 as the bog-standard Qantas Club has an annual fee of $540 for existing club members or $600 for new members. The same applies to ministers accepting business and first class upgrades, Virgin’s Beyond Lounge, and free tickets and hospitality to premium sporting events and musicals. |

3. Remove the need to prove intent to hide interests

For an MP to be found guilty of serious contempt and dealt with, the privileges committees need to prove someone has ‘knowingly’ not disclosed their interests.

Short of an MP admitting they have deliberately hidden their interests, or documentary evidence that they have done so, intent is difficult to prove.

We recommend the introduction of a strict liability rule as applies to speeding offences, where a speeding driver is fined even if they had no intention of exceeding the speed limit or were not aware of the limit.

Surely an MP’s failure to disclose a significant interest such as a house (who forgets to declare one?), or the routine failure to declare interests within the required timeframes, should be grounds enough for an investigation.

4. Mandate the disclosure of interests

A related flaw in the disclosure system is that parliamentarians have very broad discretion in interpreting the disclosure rules to decide whether their interests need to be disclosed.

For example the Senate handbook Registration of Senators' Interests states:

"It is the responsibility of individual senators to interpret the resolutions and to determine which of their interests fall within its terms, rather than relying on external advice about what ‘should’ or ‘should not’ be declared … In the end, each senator must make his or her own decision as to interests which fall within the terms of the resolutions."

The House of Representatives adopts a similar approach.

While there will sometimes be questions about whether low value interests like an old second-hand car needs to be declared, there shouldn’t be any discretion for the disclosure of valuable or significant interests like a house, directorship, shares, trust, gifts, sponsored travel and hospitality.

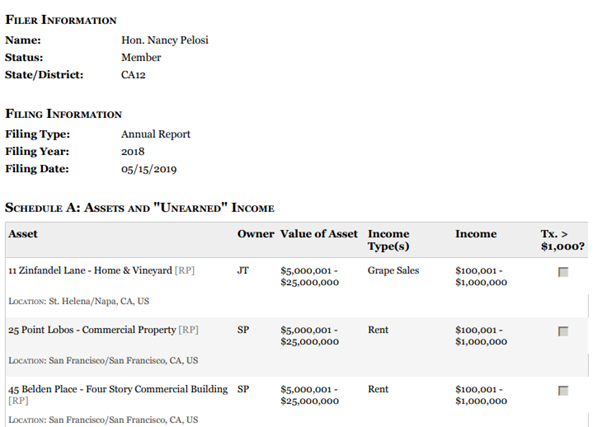

5. Require the disclosure of asset values and liability amounts

Parliamentarians would be required to disclose the value ranges of their assets, liabilities and external income to help detect unusual wealth accumulation during someone’s time in parliament.

The reform is modelled on the US Congress where members are required to disclose in their personal financial disclosure reports the value of any real estate, investments, external income, and liabilities.

For example former House speaker Nancy Pelosi's 2018 financial disclosures provides detailed financial information on her, and her husband's, financial affairs.

6. Require disclosure of share and investment transactions

Unlike the US Congress, the Australian parliament’s disclosure rules only require MPs to declare what companies or funds they have holdings in, not the value of each investment or information about the size and date of trades.

Requiring this information will reduce the potential for parliamentarians to profit from impending government decisions that may impact the share prices of certain companies or industries.

The rule would also limit the ability for ministers to make decisions which could favour their families’ investments. (The ministerial code of conduct discourages ministers’ families from investing in companies “in their area of responsibility”.)

For equity investments, parliamentarians would be required to disclose full identifying information about their holdings, including share market codes, ABNs or fund codes.

7. Require disclosure of senators’ family interests

In contrast to MPs, senators are not required to publicly disclose the interests of their spouses/partners and dependent children. This means the public knows almost nothing about the family interests of 76 parliamentarians, nine of whom are ministers in the Albanese government and 10 of whom were in the Morrison ministry.

Although senators are required to declare their family interests to the register, this information is kept hidden from public view, with the Committee of Senators’ Interests only disclosing senators’ family affairs in exceptional circumstances where it determines there is a conflict of interest.

Open Politics also recommends the following changes to standardise and improve disclosure rules for MPs and senators. (The first two would be moot if a ban on gifts, travel and hospitality is introduced.)

Disclosure of Qantas Chairman’s Lounge and other common benefits

The Explanatory notes for the Register of Senators’ Interests was bizarrely amended a few years ago to state, “there is no need to include entertainment or benefits received in common with significant numbers of other senators or other persons, such as a reception or dinner hosted by a High Commissioner or Ambassador, or access to airline lounges.”

Huh? If a foreign official or corporate influence peddler like Alan Joyce is providing generous hospitality and gifts to a lot of senators, the public really needs to know about it.

Details of gifts, travel and hospitality

As with MPs, senators would be required to disclose the values of gifts and dates they are received.

All parliamentarians would be required to disclose the values and dates of any sponsored travel and hospitality (Category 12).

Standardise the 13th interest category

The members’ register requires MPs to declare organisation memberships in category 13, while in the senators’ register this category requires senators to declare any organisations they are office holders of or have donated to.

A standard category should be created called ‘memberships and donations’.

8. Require real time disclosure

MPs are allowed 28 days to declare to the registers any changes to their interests and senators have an even more generous 35 days. These timeframes were reasonable in the pre-internet age of the 1980s to early 1990s, but they can hardly be justified today.

The Albanese government has committed to ‘real time’ disclosure of political donations and the Parliamentary Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters also recommended this in their June 2023 interim report on the conduct of the last election. Although the report did not define ‘real time’, it noted that submissions to the inquiry variously recommended that real time disclosure be deemed as within 24 hours, 5 days, 7 days, or 21 days.

Open Politics recommends a 7 day timeframe for declaring alterations to interests.

We also recommend a shortening of the timeframes for MPs and senators to lodge their initial statements of interests after an election. MPs have 28 days to lodge their statements after making an oath or affirmation as a Member of the House of Representatives, and senators have 28 days after the first meeting of the Senate or, in the case of a casual vacancy, 28 days after they’ve made an oath or affirmation. This should be reduced to 14 days.

9. Require the completion of all fields in disclosure statements

MPs and senators regularly neglect to provide relevant information on their interests, such who provided them with gifts, free travel and hospitality. Disclosure statements should be automatically rejected if there is missing information in required fields.

10. Record date statements received by register to avoid gaming

The registers do not record the date that interest statements are lodged, only the date of processing. While statements are dated by parliamentarians’ offices, this is not necessarily the date of lodgement, with Open Politics aware of numerous instances where statements have been backdated to hide breaches of the 28/35 day rules.

11. Create a fully searchable database of interests

Although the Senate introduced a database for senators’ interests in July 2023, the search feature is woeful (by design?), with search results not highlighting where key terms can be found in senators’ interest statements.

Meanwhile the House of Representatives, where two thirds of parliamentarians sit, has no plans to create a searchable database for the members’ register.

Open Politics also recommends an email alert system to notify subscribers when a parliamentarian updates their interests.